One mid-June madrugada, I finally landed at São Paulo-Guarulhos International Airport. “Madrugada” is one of those words that doesn’t have an English translation, but my personal translation for it is “the butt crack of dawn.” The morning prior, I woke up bright and early, on just a few hours of sleep, to make it to the Bogotá airport in time for my flight. I was on time, my flight, however, was not. That delay caused me to miss my connecting flight and had me spending six wifi-less hours at the Panama City airport, then catching a red-eye to São Paulo. Also, is it still considered a red-eye if the sun isn’t even up yet when you get to your destination?? It was 5 am when I was finally crawling in to bed in my new apartment. I closed my eyes and thought to myself as I drifted to sleep, work starts in 5 hours.

After six months of working remotely, traveling the world, and shuffling back and forth to DC doctors (a frustrating addition I had not planned for my beloved nomad year!), my body really caught up to me. I was tired! And while I was beyond excited to finally be in Brazil, a country I had initially considered moving to rather than spending the year traveling, I knew that something had to give.

About a month prior to this moment, I had spent a Saturday afternoon roaming art galleries in Toronto, Canada. I posted some highlights on my Instagram with the caption “saturdays are for art galleries.” I hadn’t intended it as anything particularly meaningful, but its rare that life’s callbacks are recognized in the moment.

I was fortunate in São Paulo to really adore my new apartment. Of all of the temporary abodes I’ve experienced up to this point, this apartment is one of the few that I could see myself living in long-term. Something about the layout immediately made me feel at home, so I went about the business of forging a “regular” life in it. I began establishing routine in my life, something that had been conspicuously, yet happily absent over the last several months. But this time, instead of going to events and sites at every opportunity, I found myself exploring the nearby grocery stores.

I began cooking everyday, exercising regularly, rededicating myself to my Portuguese study, reading for fun, and resting. In addition to this much-needed recalibration, I accepted that I did not need to do and see absolutely everything the country had to offer, so I reprioritized my Brazil bucket list. Priority #1: I had already planned a work-free long weekend vacation to Salvador da Bahia; I knew I could not leave the country without bearing witness to this historic city known as the Little Africa of Brazil. Priority #2: Learning about diaspora history and culture; I booked Black culture walking tours through the Afro-tourism company Guia Negro in both São Paulo and Salvador. Priority #3: Saturdays would indeed be for art galleries.

So, in addition to rest and rejuvenation, here is how I spent my Saturdays in São Paulo, Brazil.

On Saturday #1, I quickly realized that there was something intangible that I admired about São Paulo. My first stop was Museu Afro Brasil. Not only is this museum a mecca of African and African diaspora culture with thousands of works in diverse collections, it is also located inside a magnificent nature park. There’s something significant about this museum providing a space to immerse in Black culture, both indulging in the joys and reckoning with the tragedies of history and modern life, then stepping outside, finding a quiet place to sit and reflect, and feeling the earth below your feet, hearing the birds chirping around, and gazing at the peaceful lake. It feels eerily well thought out, yet magically serendipitous.

Saturday #2 was a special one. It was the one when I found myself mesmerized by the bohemian beauty of the city’s Jardins neighborhood and thought to myself, I could live here. Everything about this day felt familiar, like I could make a home here. From brunch at Botanikafe, to my afternoon at Museu de Arte de São Paulo, to my pitstop listening to Nalla on Avenida Paulista, it all just felt right. Feeling encouraged by my day, in the taxi ride home I worked up my courage, waited until we were 10 minutes away from my apartment, then nervously leaned forward to my driver and asked “posso praticar português com você?”

Saturday #3 was the day I knew I would be back. It was on Saturday #3 that the vastness of São Paulo, and of Brazil in general, became tangible to me.

People often say “you don’t know what you don’t know,” but seldom talk about the moment when you begin to realize that what you don’t know exists, when it starts to immerge into your consciousness and becomes capable of holding hopes and dreams. As I meandered through the Memorial da Resistência de São Paulo, a museum memorializing a resistance movement I had only a very vague knowledge of even ever occurring, something clicked in me. I knew, with a knowledge not housed in the mind, but somewhere much deeper in my being, that I would be back to São Paulo one day. Only time will tell if it will be to live or to visit, but on Saturday #3, I inventoried in my heart a newly actualized resolve to be a local here one day. I want to know the unknown.

On Saturday #4 I knew I was in love. It was my last day in beautiful São Paulo and as I sat in the back of a taxi, gazing out the window at the romantic couplings of trees and skyscrapers both stretching to the skies, I knew. This feeling right here, this feeling is love. I did my best to enjoy the day, I ate at my favorite restaurant, I strolled my favorite neighborhood, I really just took it all in.

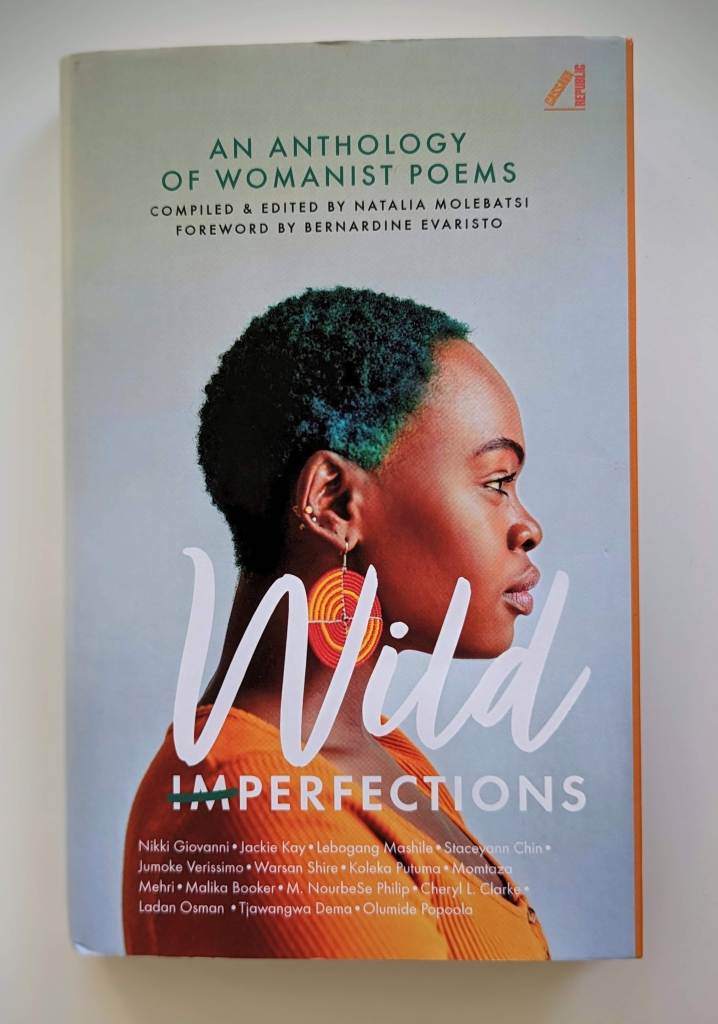

I’m usually not one for souvenirs, but I left São Paulo with one memento: a book. I first learned of Lélia Gonzalez almost two years ago when I started my coursework in Afro Latin American and Caribbean Studies. As I learned more about her politics and her work, I was increasingly blown away that I had never heard of her before. How could I call myself a womanist and not know Lélia Gonzalez? As I made my way through the program, I remember being struck by the reoccurring realization of how language barriers separate Black movements and impede sorority and coalition building across linguistic lines. I’m often frustrated by the exclusivity (in an international context) of US Black movements, but this was the first time that I caught a glimpse of all the knowledge I was missing out on. It was then that I started learning Portuguese. So one Saturday in São Paulo, I made my way over to gato sem rabo, a bookstore that exclusively sells books written by women authors, and picked up the book collection of writings and speeches by Lélia Gonzalez. I figure, what better way to practice my Portuguese than through the words of a revered radical Black activist.

The funny thing about Saturdays 1 and 2 is that on both occasions I had fully intended to explore more of the city on Sunday as well, but when Sunday rolled around I was simply too tired. So, I listened to my body, and by the time Saturday #3 came around, I learned my lesson and basked in the glory and gratitude for the Saturday without envy for anything more.

São Paulo confirmed to me that I’m a city girl at heart. Little did I know, all I needed was a few weeks in the biggest city in the Americas to help me get back to myself, reset my mind and body, and feel inspired to continue learning. I’m forever grateful for this city, and I look forward to my return.

Signed,

N.A.